(c) Nico99 / Stock.Adobe.com

ETHNOMIMETICS VS biomimETICS

Ethnomimetics vs Biomimetics – Some Brief Definitions...

Biomimetics: Biomimetics involves drawing inspiration from the essential properties of one or more biological systems to develop processes and organizations that support the sustainable development of human societies (source: ISO 18458 standard, French Ministry of Ecology, 2022).

Biomimetics is a strong interaction between life sciences (biology) and engineering sciences.

Ethnomimetics: Ethnomimetics draws inspiration from humans and their knowledge, particularly the materials and techniques developed by various so-called “traditional” or “Indigenous” societies.

Ethnomimetics is a strong interaction between engineering sciences and the human sciences (anthropology and ethnology, archaeology, museology, and Indigenous knowledge systems).

(Source: Ethnomimetics — Wikipedia)

The following discussion is extrated From the article by Martin Koppe, originally published in:

URL source: https://lejournal.cnrs.fr/articles/regard-anthropologique-sur-le-biomimetisme

From industrial adhesives inspired by gecko feet to traditional dances mimicking animal movements, humans draw endless ideas from nature. Yet, this biomimicry often reveals fascinating social mechanisms... A conversation with anthropologists Perig Pitrou and Lauren Kamili...

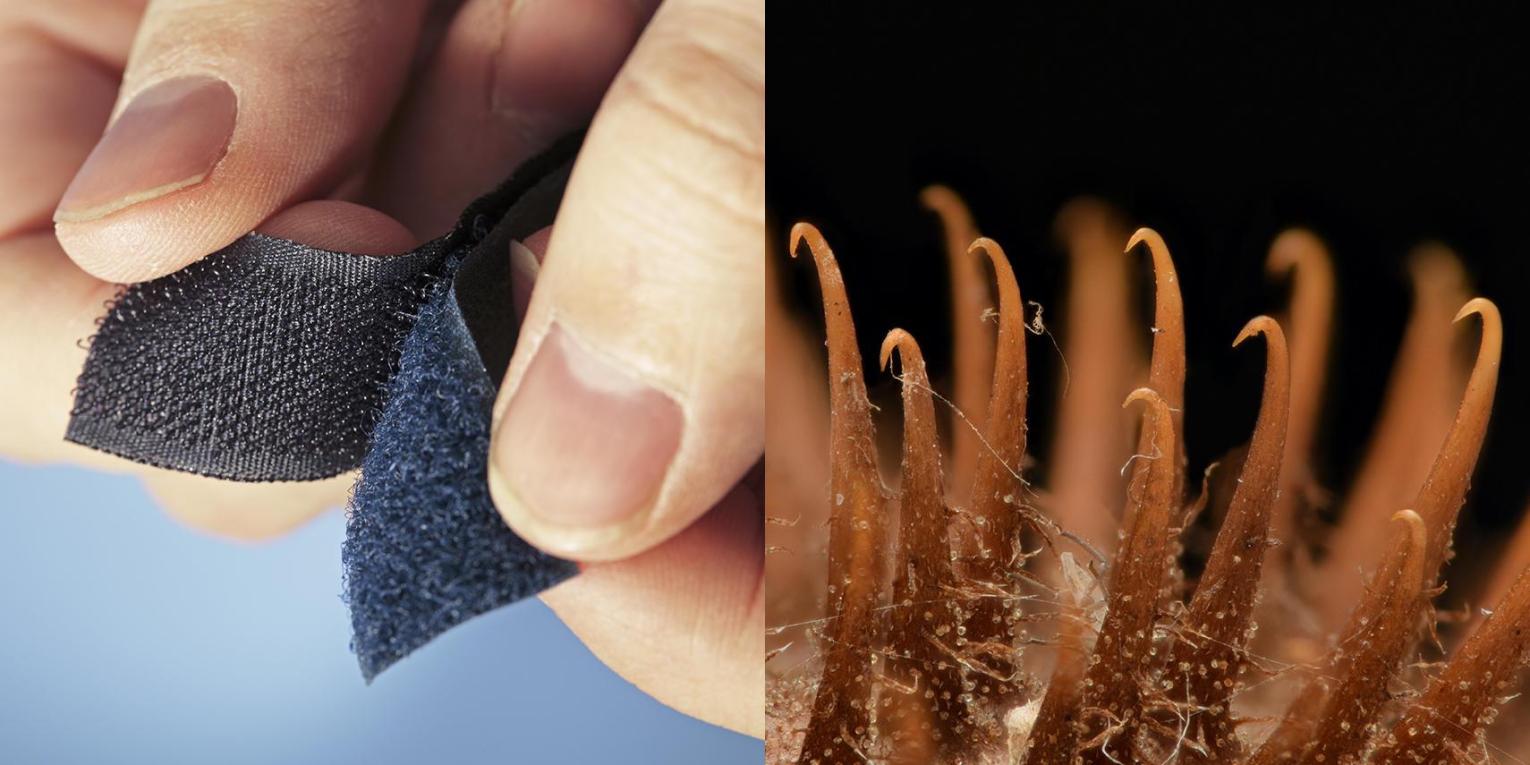

We’re all familiar with the story of Velcro, whose tiny hooks were inspired by the burdock plant, or of swimwear designs mimicking the rough texture of shark skin. Biomimicry is this approach to technological innovation and engineering that draws inspiration from the shapes, materials, and systems of living organisms. But what are the origins of this concept, and what else does it encompass?

Lauren Kamili: The term first appeared in 1969, coined by biophysicist Otto Schmitt, but it gained momentum in the late 1990s, as ecological and social crises and the depletion of natural resources pushed the search for less destructive societal models. A major turning point came with the 1997 publication of Biomimicry: Innovation Inspired by Nature by American biologist Janine Benyus. She defined biomimicry as “the conscious emulation of life’s genius, innovation inspired by nature.” For her and other contemporary practitioners, life on Earth represents 3.8 billion years of research and development. She also introduced what she called the “Life’s Principles”: using solar energy, producing no waste, recycling everything…

Perig Pitrou: Ecology, however, is not always the primary concern when drawing ideas from nature. One can easily adopt a “bio-inspired” approach—observing natural systems to create objects that may not necessarily be environmentally friendly. For instance, technologies that imitate photosynthesis might still be harmful if they rely on toxic chemical components. In contrast to simple bio-inspiration, biomimicry is sometimes seen as a more holistic project, in which human-made objects are designed to reintegrate into natural cycles without causing pollution.

The tiny hooks of Velcro were inspired by the barbs of the burdock fruit (right).

Stocksnapper; Constantincornel/Stock.Adobe.com

The field is mostly associated with natural sciences and technological innovations. As anthropologists, how do you approach the question of biomimetics?

P.P.: Indeed, the human and social sciences have only recently begun to engage with this topic, which led us to organize an interdisciplinary conference on the subject. In the "Anthropology of Life" research group I lead, our goal is to understand how conceptions of life and living beings vary across time and space, depending on the technical activities and collective projects developed by different human societies. Biomimicry offers an interesting lens to explore both these technical and social dimensions. Imitation is not a direct replication of nature—it requires a sequence of steps and operations: observation, measurement, drawing, project identification, and possibly, the construction of objects. We seek to examine the entire operational chain behind it. Likewise, nature should not be imagined as a teacher dispensing lessons; rather, it is humans who select and identify which elements are most relevant to imitate.

The two main criteria humans use in this process are efficiency (for example, mimicking the shape of a kingfisher's beak to improve the aerodynamics of a high-speed train) and symbolic value (such as imitating the movements of an animal in an initiation ceremony to embody its qualities). We therefore advocate for a broad understanding of biomimicry, one that includes practices from diverse societies. It is important to remember that the imitation of nature is ancient and not limited to Western societies or technological advancement. This is one of the key lessons of ethnology.

Based on your work as an ethnologist, can you give us an example?

P.P.: Humans do more than imitate living beings—they may also mimic ecological systems. During fieldwork in the Mexican state of Oaxaca, I observed certain Indigenous communities performing rituals of miniaturization. On small-scale representations of their landscapes or fields, farmers distribute maize and water, symbolizing rain. These setups can be interpreted as a manifestation of the human capacity to imitate large natural cycles—a desire to become the cause that allows life to flourish. The imitation of nature is a universal human practice, but always shaped by the specific goals and projects of each society.

Ritual offering performed among the Mixe of Oaxaca, Mexico. (Périg Pitrou).

How do you concretely identify an approach that imitates nature?

P.P.: It involves gathering observations and conducting experiments. Anthropology relies on ethnographic fieldwork, documenting the places where biomimetic practices occur. This can take place in the Amazon, as Philippe Descola demonstrated by showing how the Achuar cultivate their gardens by modeling them after the forest. Investigations can also be carried out in scientific laboratories. Lauren Kamili belongs to a new generation of interdisciplinary researchers who must become fluent in scientific vocabulary—just as others learn vernacular languages—in order to conduct their work effectively.

L.K.: During my PhD, I will be conducting fieldwork at the Laboratory of Bio-inspired Chemistry and Ecological Innovations, led by Claude Grison. This lab studies how plants store and accumulate heavy metals, with the goal of designing protocols to decontaminate polluted mining sites. I will observe the researchers’ approaches and the ethical questions that may arise—for instance, if potentially invasive plant species are used.

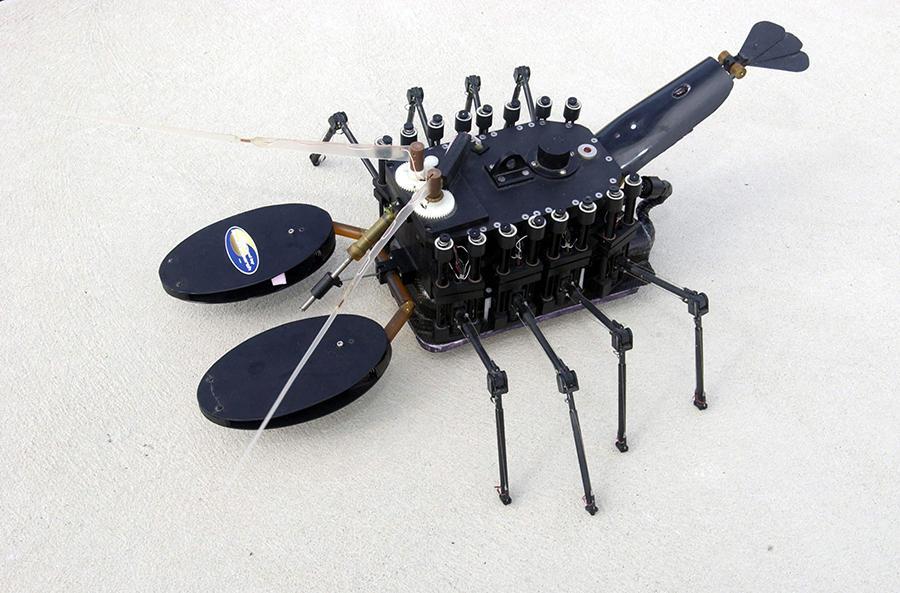

I am particularly interested in how cultural and social values—sometimes quite diverse—influence the perception of nature within contemporary biomimicry. Although not always well regarded by the broader academic community, the military is a notable example of biomimicry driven by less peaceful intentions. Among our invited speakers, Elizabeth Johnson from Durham University devoted a chapter of her dissertation to U.S. military labs studying how lobsters move from water to land in order to design robots that can assist with troop landings.

A biomimetic lobster robot, RoboLobster, displayed at the Marine Science Center of Northeastern University in Nahant, Massachusetts, in September 2004.

These robots take advantage of abilities proven in animals to navigate real-world environments.

Jodi Hilton / The New York Times / REA.

What place does biomietics hold in Western capitalist societies?

P.P.: To fully grasp the complexity of biomimicry, it’s important to observe the actors and their projects in all their diversity—both in modern Western societies and in traditional ones. Some initiatives are explicitly driven by profit motives, while others are based on citizen science perspectives. Here again, attention must be paid to the wide range of models followed by groups that identify with biomimetic approaches. In the background, it’s the underlying conceptions of nature that must be decoded.

When observing the living world, humans may focus on peaceful relationships—such as exchange or symbiosis—but antagonistic relationships like predation are also sometimes emphasized. As a researcher working in the anthropology of life, I am interested in the conceptions of life underlying the techniques and collective projects pursued by human groups who take nature as a model. Depending on its cultural choices, each society does more than simply select certain aspects of the living world to manufacture artifacts—it also finds inspiration to construct a social order, which may involve distancing itself from the natural order.

How is the biomimicry community structured and organized in France?

L.K.: A wide variety of actors identify with biomimicry: companies, public laboratories, citizen associations… This has resulted in multiple communities, each with its own set of values. However, many of these actors converge around the European Center of Excellence in Biomimicry located in Senlis. This organization, for example, collaborated with the French Standardization Association (AFNOR) to help establish an ISO standard for biomimicry. The cooperative society Terre Vivante is an alternative actor within this network, offering a different value framework.

P.P.: These collectives vary greatly depending on the socio-economic model they aim to promote. The idea of reconnecting humans with the natural environment often involves reclaiming knowledge and know-how linked to the living world. Alongside engineer-driven models, other forms of biomimicry associated with “do-it-yourself biology” emphasize hands-on experimentation and invite individuals to observe and interact with living organisms. Within the scientific community, biomimicry brings together chemists, biologists, physicists, and roboticists. The CNRS recently launched a call for research projects on the topic, which generated a wide range of subjects—from the study of sea urchin coloration to the design of mechanical parts inspired by bone structures. Each laboratory follows its own vision of biomimicry, but it’s encouraging to see the CNRS fostering collaboration among them. Ultimately, scientists could develop methodologies capable of guiding interdisciplinary research in this field.

And what is biomorphism?

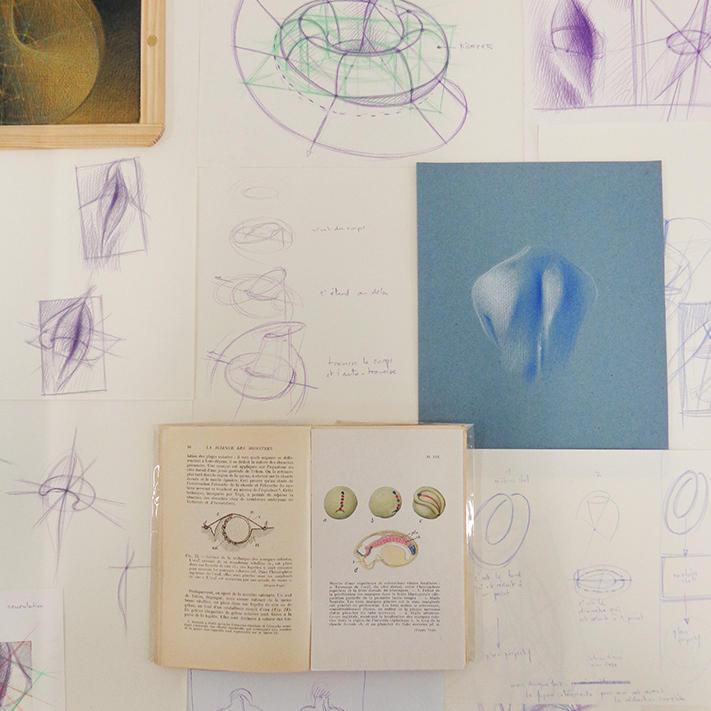

Living organisms have always been a source of inspiration for artists. The members of the collective “Biomorphism. Sensitive and Conceptual Approaches to the Forms of Life” have chosen not to focus on “realistic” images in which we immediately recognize the familiar outlines of living forms we encounter in our daily environment. Instead, they use a variety of approaches—changes in scale, abstraction, poetic symbolism, morphological studies, etc.—to reveal more complex and hidden aspects of the living world. The goal is to construct and convey collective, transdisciplinary representations of life in its specificity, in keeping with the urgent challenges of coexistence among all living beings within the Earth’s ecosystem.

Detail of a display case showing morphogenetic studies by Sylvie Pic, head of the Biomorphism program.

She explores the relationships between body and space through a sensual and phenomenological treatment of transforming mathematical surfaces.

© Sylvie Pic

Notes:

1 Lauren Kamili is a PhD candidate at the École des hautes études en sciences sociales (EHESS). Her doctoral research is funded by the French Environment and Energy Management Agency (ADEME).

2 Perig Pitrou is a research director at the Laboratoire d’anthropologie sociale (a joint unit of CNRS/Collège de France/EHESS), where he leads the “Anthropology of Life” team. He was awarded the CNRS Bronze Medal in 2016.

A CNRS/University of Montpellier joint research unit.

3 Researcher at the Laboratory of Ethnology and Comparative Sociology (a CNRS/University of Paris Nanterre unit).

4 Program supported by AMU/CNRS/Carasso Foundation.

Home